The Decline of the Sheep Fiber Industry in Western North Carolina: By the Numbers

Image courtesy of Southern Appalachian Digital Collections.

By Coral Ferris-Merendino

The sheep population and wool production data from the National Agricultural Censuses from the years 1840 to 1978 detail a story consistent with what is described in other primary and secondary sources. According to a majority of sources, the sheep and fiber industries peaked in Western North Carolina in the years between 1870 and 1900.[i] This can be attributed to the importance of sheep in an agrarian lifestyle in areas where typical farming was not as profitable or feasible[ii] and the handicraft revival movement of the 1890s.[iii] Between 1910 and 1925, the sheep meat and fiber industry saw a significant downturn in the region.[iv] This can likely be explained by the encroachment of outsider industrial companies onto land that was previously commons for grazing and industrialization of the workforce.[v] Along with the first World War, this likely created a rift between farmers and their farms both economically and culturally. The number of sheep and pounds of wool produced in Western North Carolina increased briefly in 1930 as it recovered from the First World War in part due to cooperative institutions established for the sale of wool and lamb.[vi] However, the sheep fiber industry was then seemingly diminished by competing industrial pressures, the Great Depression, and the second World War.[vii] Production in the sheep industry rose once again in 1959, which can be attributed to the financial assistance granted by the National Wool Act of 1954.[viii] In the end, the sheep fiber industry in Western North Carolina could not remain suitably profitable in such a competitive market coupled with a lack of demand, so it faded away.[ix]

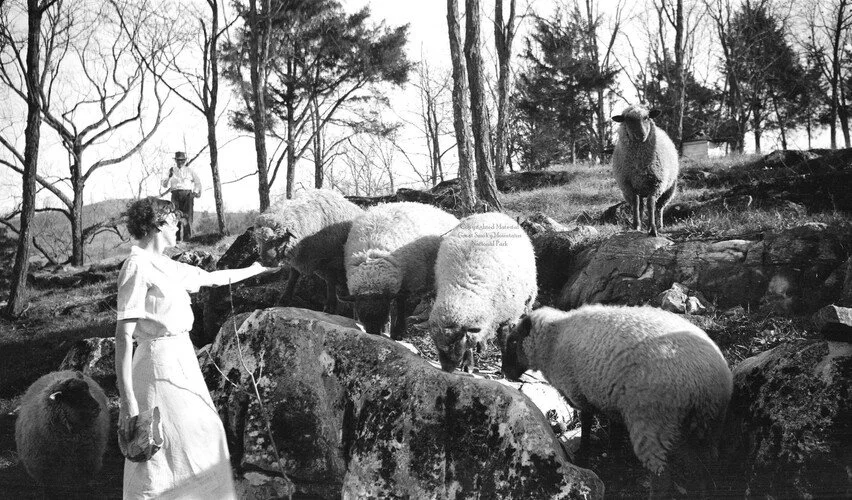

Sheep grazing. Image courtesy of Southern Appalachian Digital Collections.

The sheep fiber and meat industry began far before 1840, as the 1840 National Agricultural Census indicates that there was a sufficiently thriving industry at that time. In 1840, there were already 25,891 sheep in total in western North Carolina, including Buncombe, Cherokee, Haywood, Henderson, and Macon counties.[x] What caused sheep raising to be so accessible in Western North Carolina over other agriculture practices like tobacco that could have been more economically profitable? Some sources like the work of Mary Beth Pudup and Tracy Turner Jarrell offer the explanation that the rough, mountainous terrain of the Southern Appalachians encourages raising sheep in comparison to crop agriculture, attributed to the poor soil and the rocky, steep slopes of the mountains and hills which make row crop farming difficult or impossible.[xi] Donald Edward Davis furthermore explains that in comparison to many crops, sheep are uniquely able to traverse the Southern Appalachian environment and can fully utilize grazing areas in otherwise unfavorable common spaces.[xii] Davis also describes that the use of sheep’s adaptability in such conditions is not new practice, it is instead culturally descended from the herding practices of the Scots-Irish, who brought their experience of shepherding in the mountainous environment of Scotland and Ireland to America when they immigrated.[xiii] Their culture and experience led to sheep raising emerging as a key industry in the geographically similar terrain of the Appalachians. This paired with its profitability led to sheep fiber and meat production becoming a critical industry, both culturally and economically, significantly contributing to the slow, steady climb of the sheep population in Western North Carolina between the years 1840 and 1880. In the region, the number of sheep increased from 25,891 in 1840 to 70,310 in 1880, more than doubling the population.[xiv]

An important element of sheep husbandry was the common areas available to sheepherders. At the time, much of the mountainous land that sheep grazed upon was either unclaimed or unmonitored by private owners and was, thus, used by the general public as a grazing commons. Pudup writes that such lands were not beneficial for much else, as it was often too far from current settlements for reasonable housing and too rugged for plant agriculture.[xv] This allowed small rural farmers to graze a large number of sheep without having to own a significant amount of land, invest in expensive fencing, or having to provide feed for the majority of the year. Sheep also presented a unique opportunity as a form of double income for small farmers. Sheep can be culled for meat, bred for lamb, and shorn for wool, providing farmers with multiple different markets to profit from during different parts of the year. This means that a single herd of sheep can provide many diverse revenue streams over time to better support the farmer. This made sheepherding very attractive to rural farmers who wanted to maximize their time and limited resources. Jarrell explains that multiple farmers claimed that one thing that made sheep farming uniquely beneficial was that the money made from the shorn wool could pay for the upkeep of the flock, and the lambs sold for meat could be sold for a profit for the farmer.[xvi] This meant that sheep raising was not only a form of subsistence agriculture, but one that was beneficial in a capital-based economy.

After 1880, the number of sheep started to steadily decline in the region, though this trend was not mirrored in wool production. As sheep numbers decreased in Western North Carolina from 70,310 in 1880 to 58,385 in 1900 the amount of wool inversely rose from 117,251 pounds to 155,370 pounds.[xvii] Frances Louisa Goodrich explains in her book Mountain Homespun that this increase in demand for wool is likely due to the handicraft revival movement of the 1890s that was occurring in Southern Appalachia.[xviii] This movement led to a change in wool harvesting and weaving practices, shifting from being mostly for the production of private, family-kept goods, selling excess wool to be processed elsewhere in the north, to producing complete garments for sale in markets. Goodrich further details that this shift meant it was more profitable for small wool producers to have fewer sheep that produced a higher quality of wool to be turned into more expensive, higher profit garments.[xix] The handicraft revival movement provided rural communities with craftsmen and the means to clean, process, dye, and weave the wool they produced. This venture was previously completely unfeasible due to a lack of sufficient infrastructure.

Frances Goodrich in front of woven wool coverlets. Image courtesy of Southern Appalachian Digital Collections.

This increase in pounds of wool produced but decrease in the number of sheep may have another cause—the encroachment of large private industries onto previously common lands. During this period, large companies looking to fervently exploit natural resources became increasingly common. Companies like the W.M. Ritter Lumber Company began buying large amounts of land to privatize for logging and coal operations. This meant the land was no longer available as common spaces, which sheep farmers used to graze their sheep. Without the commons, sheep owners had to own the lands that they grazed their sheep on, along with investing in fencing, which significantly increased the cost to keep and maintain a flock. This would have made sheep herding significantly less profitable and likely led to many individuals leaving the industry. It is explained in the The W.M. Ritter Lumber Company Family History Book that the W.M. Ritter Lumber Company began operations in Swain County, North Carolina in 1903 along the Hazel Creek.[xx] During this time there was also a significant decrease in the amount of sheep being kept on farms in Swain County. From 1900 to 1910, the number of sheep in Swain County decreased from 3,429 sheep to 2,246 individuals.[xxi] This evidence indicates that as companies entered these rural communities, the opportunities and jobs they presented outcompeted the farming lifestyle. Despite the risks of such jobs, working at a lumber mill like the one located in Swain County’s Hazel Creek area gave families access to a steady wage and a more stable community.[xxii] Even for farmers who wanted to maintain their sheep, competition for land and a growing lack of common spaces meant that despite the profitability of sheep, farmers were forced to downsize.

This downward trend previously observed was highly accelerated with the First World War. The World War decimated farming practices and agricultural stability across the country. This can even be observed in the census data, as county numbers for all types of livestock were not collected for the year 1920. Using the data available for the state of North Carolina, it can be seen that the number of sheep present in the state decreased from 214,473 individuals in the year 1910 to only 90,556 sheep in 1920, a decrease of more than half.[xxiii] According to the supervisor commentary on observed trends in Appendix B of the 14th Census, this may have been due to men being drafted into the army. Farms either had to downsize their numbers or cull their herd entirely due to the lack of labor force.[xxiv] Men were not only forced into the draft but heavily encouraged to work in industrial centers and factories that were seen as more beneficial to the country in order to help with the war effort. This was a massive blow to the entire agricultural industry and caused such a severe decline in the sheep industry that it would never recover to its former size. Even after the war when agriculture began to recover, farms were still significantly affected. Men returning often decided to leave agriculture entirely and instead moved on to jobs that were not so intimately crippled by the neglect inflicted due to the war. Those who stayed often downsized as commercial fertilizers were becoming more common—with this advancement, farmers were expected to produce more products on a smaller amount of privately owned land.[xxv] The private model was not profitable or feasible for rural sheep-herders in the same way commons-focused practices were. These factors led to a significant migration of previously rural farmers moving to more profitable industrial towns, leaving their previous agrarian lifestyle behind, often indefinitely.

Fiber processing at Biltmore Industries. Image courtesy of Southern Appalachian Digital Collections.

After the devastating blow that was the period between 1910 and 1925, 1930 saw an important increase in both sheep population and wool production. In western North Carolina the number of sheep on farms increased from 15,119 individuals in 1925 to 30,140 sheep in 1930, nearly doubling the previous low.[xxvi] This increase occurred during a brief recovery period between the First World War and the eventual Great Depression and the Second World War. During this period, sheep farming seemed to be a highly productive and lucrative practice for similar reasons as it was in the past. At this time cooperatives were being formed between sheep farmers in local communities to make selling wool and lamb more profitable. By working together they could form lamb and wool pools in order to ensure quality and quantity to get a higher price on the larger market. Jarrell describes one example of such cooperatives, the Watauga Wool Pool, which collaborated both within and outside the county to sell tens of thousands of pounds of wool and held auctions sold wool for significantly more profit than an independent farmer could manage.[xxvii] Local farmers could collaborate and sell to wider markets with large needs which allowed even small, local sheep fiber production to flourish for a short time in western North Carolina.

Despite this effort, sheep alone were not economically viable. During this time, sheep were raised in conjunction with agriculture and other livestock to make the agrarian lifestyle viable as both a commercial and subsistence endeavor.[xxviii] This did not last, however, as the 1935 census displays a significant downturn in sheep and wool numbers. According to the National Agricultural Census from 1930 and 1935 the number of sheep in Western North Carolina decreased by 15,900 individuals.[xxix] This can likely be attributed to the Great Depression. Beginning in 1929, the effects of the economic crisis could now be seen clearly in the sheep population numbers of the 1935 Agricultural Census. Sheep numbers continued to decline from 14,240 individuals in 1935 to 8,040 in 1940.[xxx] It is likely that the economic downturn crippled the markets that the lamb and wool pools relied on to remain profitable, leaving farmers with no other choice but to downsize to cater to more local, accessible, and stable markets. This decrease was only accelerated in the following years, as the Second World War diminished the industry with another overwhelming shift away from agrarian life, similar to the decrease seen during and after the First World War.

The years between 1945 and 1954 saw the numbers of sheep and pounds of wool in Western North Carolina relatively stabilize. The numbers at this time were diminutive, with Swain County notably only having two sheep present in the year 1954.[xxxi] This changed in 1959, as Western North Carolina saw nearly a 50% increase in sheep populations between 1954 and 1959.[xxxii] This is likely due to the National Wool Act of 1954. This Eisenhower-era act made it so tariffs were placed on imported wool and wool products, while also providing support payments to local wool producers.[xxxiii] This revitalized the sheep fiber industry throughout the country. In Swain County alone, the number increased to 225 sheep in 1959, a stark contrast to the previous two. A similar drastic increase was observed in Buncombe and Haywood coutnies, though all counties in Western North except four saw sheep population increases. This boom in the industry provided by the National Wool Act was only temporary. During the 1964 Agricultural Census, the numbers once again saw a significant decrease from 6,686 sheep in 1959 to 2,602 in 1964 in Western North Carolina.[xxxiv] Despite the subsidies, the need for a large amount of private land to raise a profitable amount of sheep was not feasible for smaller farmers, leading to smaller farms around western North Carolina being out-competed by wool-producing operations elsewhere in the country. The downward trend only continued into the 1970s with the ever-expanding use of synthetic materials for textile use and other competing markets. Small-scale wool production eventually became entirely economically unfeasible.[xxxv] By 1978, no western North Carolina county had more than 300 sheep, and the region altogether had less than 600 individual sheep.[xxxvi]

The fiber industry in western North Carolina is defined by its broad ebbs and flows, shifting with changes in national politics and industry support. There is an evident lack of National Agricultural Census data in the years before 1840. If this data could be recovered, it could show even more patterns regarding the amount of wool produced and the number of sheep kept in Western North Carolina. Accessing this data could give a more complete picture of the full history of the sheep fiber and meat industry in the region, providing an important glimpse into the conditions surrounding the early years of the industry. There is also the matter of the viability of the industry. It is possible that the sheep fiber industry was never meant to be viable in western North Carolina—although the industry could also be a victim of inopportune scenarios. There were two main points in history where a significant effort was made to try and make wool production economically viable—the local scale in the form of wool pools in the 1930s, and the national scale in the form of subsidies given out to farmers from the National Wool Act in 1954. Independently, these efforts had a significant amount of success, but they were unable to maintain it. The issue may be the efforts were misaligned. Could it be possible if these efforts were more concentrated and closer together, the sheep fiber industry in Western North Carolina could have recovered from the economic depression and the World Wars?

[i] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1840 – 1900.

[ii] Mary Beth Pudup, “The Limits of Subsistence: Agriculture and Industry in Central Appalachia,” (Agricultural History 64, no. 1, 1990), 68.

[iii] Frances Louisa Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun : A Facsimile of the Original Published in 1931,” (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989), 17.

[iv] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1910 – 1925.

[v] Dennis E Reedy and William McClellan Ritter, “The W.M. Ritter Lumber Company Family History Book,” (1983).

[vi] Tracy Turner Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production in Watauga and Ashe Counties in North Carolina from the 1930s to Now, “ (Appalachian Journal 38 (4)), 369.

[vii] Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun,” 21; USDA Census of Agriculture, “Fourteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1920, Volume V. Agriculture, Appendix B. – Extracts from Supervisors’ Correspondence Relative to Decrease in Number of Acreage of Farms,” 920.

[viii] Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production,” 372.

[ix] Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun,” 64.

[x] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1840.

[xi] Pudup, “The Limits of Subsistence,” 68; Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production,” 366.

[xii] Donald Edward Davis, “Where there are Mountains: An Environmental History of the Southern Appalachians,” (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000;2011), 101; Pudup, “The Limits of Subsistence,” 68.

[xiii] Davis, “Where there are Mountains,” 99.

[xiv] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1840 – 1880.

[xv] Pudup, “The Limits of Subsistence,” 68.

[xvi] Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production,” 366.

[xvii] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1880 – 1900

[xviii] Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun,” 17.

[xix] Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun,” 64.

[xx]Reedy and Ritter, “The W.M. History Book.”

[xxi] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1900 – 1910

[xxii] Reedy and Ritter, “The W.M. History Book.”

[xxiii] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1910 – 1920.

[xxiv] USDA, “Fourteenth Census of the United States, Appendix B,” 920.

[xxv] USDA, “Fourteenth Census of the United States, Appendix B,” 920.

[xxvi] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1925 – 1930.

[xxvii] Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production,” 369.

[xxviii] Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production,” 365.

[xxix] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1930 – 1935.

[xxx] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1935 – 1940.

[xxxi] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1945 – 1954.

[xxxii] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1954 – 1959.

[xxxiii] Jarrell, “‘Sheep!’ Sheep Production,” 372.

[xxxiv] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1959 – 1964.

[xxxv] Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun,” 21.

[xxxvi] USDA, “National Agricultural Census,” 1978

Coral Ferris-Merendino was an undergraduate student in Dr. Manget’s Environmental History class at Western Carolina University in the Spring of 2024.